Acquiring specialty

ACQUIRING SPECIALTY-RELATED COMPETENCE IN LEARNING PROCESS OF STUDENTS

Different Interpretations of Competence; Measuring Competence

People with an education that matches higher professional level usually work in occupations that assume the ability to think, responsibility and management skills. Today’s managers are often trainers of people who are their subordinates, information providers and distributors of resources. More and more often, they share responsibilities or delegate some of it to others. Professional employees are expected to have the desire and ability to take responsibility and manage the team. Employees are responsible for consistent improvement of their skills and they’re expected to apply their knowhow flexibly and be able to co-operate, as this will result in new combinations of know-how, i.e. collective competence [60].

Pugh ja Hickson [77] refer to the opinion of McKinsey, stating that at the beginning of this millennia, 80% of the work done would rather demand brain capacity than manual skills while only 50 years ago the situation was just the opposite. Although mental work involves, without any doubt, certain technical know-how and occupational skills, it will also demand more and more abilities, skills and predisposition for acting as a leader from employees.

In all the spheres of education, above all, in professional education, more and more attention is given to general key competences or the development of trans-disciplinary qualifications.

3.1.1 Competence and Qualification

There’s lots and lots of literature about competence and qualification, however, the implementation of suggested approaches has not been consistent and there is no consensus with respect to the accurate, specific meaning. Competence and competency are synonyms.

Ellström [78], for example, gives the following definition of competence: competence is individual’s (or collective’s) potential ability to cope, successfully (according to certain formal or informal criteria, that are determine) with certain situations or perform certain task or work. This ability is determined by:

- cognitive motoric skills (e.g. manual skills);

- cognitive factors (knowledge of different type and intellectual skills);

- affective factors (e.g. attitude, values, motivation);

- personal characteristics (e.g. self-confidence);

- social skills (e.g. communication and co-operation skills).

Therefore, such a definition is task or employer-focused and will not assume leader level knowledge or skills of a person. Employees are only required to abide by work discipline and workplace rules. Why the task needs to be fulfilled, is up to the employer; professional competence is [79], according to the definition, a working relation between individual’s ability and certain task or situation, which involves:

- combining of knowledge and intellectual skills (e.g. inductive, logical), plus non-cognitive factors (e.g. motivation and self-confidence);

- proven abilities, which are a function of the five factors, listed above;

- rather potential than real ability, i.e. an ability that is, in reality, only used when certain conditions are met (e.g. task representing a challenge or work situating that is sufficiently independent).

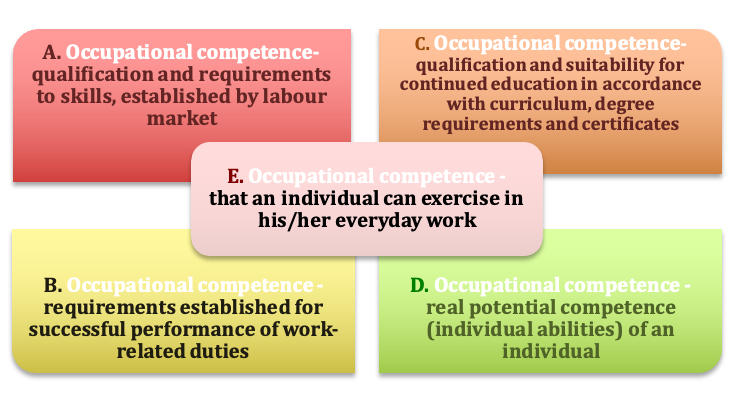

Ellström [79] defines qualification as a competence that is needed for a certain duty and/or that is, either implicitly or explicitly, defined by individual characteristics. He approaches professional competence from three different angles and gives it five different specific meanings with these three angles (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Different meaning of occupational competence [79]

Atwell [80] finds that the use of the term of competence with the meaning, defined by Ellström, will cause confusion, as the consequence of different meaning of the nature of aforementioned competence, in Great Britain, competence is seen as an ability to fulfil certain duties/tasks in accordance with certain criteria, defined by an organisation.

In Germany, however, competence is seen as individual characteristics that are linked to both knowledge and skills and involve professional identity. This is illustrated by four types of competence, distinguished by Bunk [81]:

- occupational competence: individual will cope well in a specific work-related sphere and won’t need supervision;

- methodological competence: individual will respond systematically to problems that may emerge during performance, will independently find solutions and is capable of implementing the experiences obtained in new situations;

- social competence: people communicate and co-operate with others, show empathy and skills required for teamwork;

- participation competence: people share their work and working environment, are capable of organising things and adopting decisions, being responsible for their activities and development.

According to Hövels [82], competence is a definition of Anglo-American background and relates to competence and performance theories that date back to learning and knowledge psychology. The concept of qualification comes from economics and it can be assumed that this involves the combination of acquired skills and knowledge with professional practice.

Streumer and Björkquist [83] conclude that key qualifications or closely related concepts, like general qualifications, core qualifications and transferrable qualifications, are difficult to be supplied with an European definition. However, certain properties can be attached to key qualifications.

- Key qualifications offer means for fast and efficient acquisition of specialist know-how.

- Key qualifications are more abstract than qualifications characteristic of certain profession or sphere.

- Key qualifications will allow the employees to respond efficiently (by taking initiative) to changes that take place in their work.

- Key qualifications will allow employees to control their own career.

- Key qualifications represent competence acquired that will allow a student to reach a break-through or a higher level.

These properties can be used to define an individual’s competence.

Over the last two decades, a model described by five factors (Five –factor model, FFM) to study the relations between personality and work-related performance. These five personal factors are: neuroticism, extrovertedness, openness to experiences, agreeability and responsibility. Meta-analyses, conducted since 1991, have evidenced important relations between personality and work-related performance [84].

It seems that work results are, above all, linked to responsibility or work discipline. Extrovertedness and emotional balance or emotional discipline (the opposite of neuroticism) are prerequisites for achieving success in work. Openness to experiences, however, has conflicting nature. Work results can be rather estimated on the bases of personal characteristics than cognitive abilities. People with internal peace and balance (higher mental discipline) are more free and creative in their actions. Apart work, they also visualise and achieve their objectives.

Motivational properties of occupational competences mean general tendencies of object of interest and motivation. Object of interests refers to motivation of activities. Occupational interest has been used in two ways for study purposes. First of all, an attempt was made to identify vocations/jobs, where requirements established to work and the attitude, preferences and objectives of the person studied are a good match. In case of the other approach [61], works and specialities have been categorised in accordance with different orientations (e.g. according to the Dutch hexagone, realist, investigative, artistic, social, conventional and enterprise-oriented).

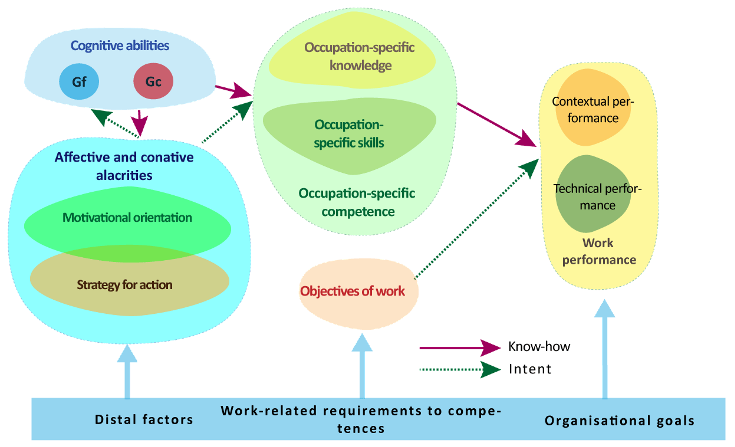

Figure 3.2 Model of occupational competence [61]

Figure 3.2 illustrates occupational competence and the background abilities/readiness to explain work performance. Working will depend on the task, needed in the process, which launches the work. Occupational competence is here treated as capacity of an individual, the real competence. Its components are occupation-specific baggage of knowledge and occupation-specific skills. Against the background of occupational competence, know-how (knowledge and skills) is cumulated through earlier life and abilities (including education and experience).

Development of competences is a constant process, involving individuals adopting and improving their skills to achieve more and more success in one or another sphere. Development of abilities and competences and acquisition of know-how will form a “chain” that the figure above describes as a path of know-how.

Competence stands for proven ability, for the purposes of ECVET and EQF, to use knowledge, skills and personal social and/or methodological abilities in work-related or learning situations and for specialty-related and personal development. The terms of responsibility and dependence are used to describe competence.

3.1.2 Intelligence and Competence

Intelligence and competences are closely linked. For example, Sternberg [85] has compared intelligence and related abilities to competence that play a material role in the development of specialist skills. According to Sternberg, IQ tests serve to measure abilities of individuals that can be developed.

Individual characteristics – for example, physical intelligence and abilities – represent an outcome of genetics and environment. Genes can be used to explain individual differences. The influence of competence and development of specialist skills on the evolvement of intelligence is impossible to measure. Thinking skills can be suggested as an example of combined effect of genetics and environment: for example, noticing and identification of problems, creation of strategies for solving problems, representation of information, guiding of resources and monitoring and assessment of solutions to problems. Sternberg [85] comments that “if we describe these meta-components of thinking as intelligence, we must also admit that intelligence is a “form” of developing competences that determine the development level of specialist skills”.

Affective (caused by affect, highly emotional, excessive) and conative (cognitive, perceptive) alacrities are very much needed, from one hand, to apply professional skills and from the other hand, for the maintenance and updating of professional skills. The influence of affective-conative factors on know-how is marked, on Figure 3.2, with the definition “path of intent”. For the purposes of occupational development, the central alacrities are, among others, performance motivation, assessment of effectiveness, internal orientation on objectives and thinking and self-regulation skills [86]. Zimmermann ja Kitsantas [87] pay attention to volitional processes: they discuss the hidden dimension of individual competence, by which they mean individual’s skill to adjust its learning and activities. Distal factors (earlier life), role requirements, related to work and organisational objectives will form a contextual framework that will, from one hand, determine alacrities and the development and shaping of competences and performances.

Work performance (Figure 3.2) is divided into technical and contextual performance. Technical performance may be related to objectives of a worker. Contextual performance will promote the effectiveness of social and organisational network and psychological climate, thus supporting the achievement of goals of the entity, commissioning the work, or labour market subjects. Entrepreneur or enterprising person will internally add up the requested work performance and personal contextual performance. Entrepreneur will perform the requested work, building his company up at the same time.

3.1.3 Summary

Competence and competencies are synonyms. The earliest approach the qualification date back to the industrial era and need expansion by the definition of quality in such a way that it would make sense in the information era where students are not prepared only to enter labour market (as someone performing the work, determined by labour market requirements), but to be an active person, capable of taking responsibility for his or her life programme in full and also for the realisation of dreams and visions.

In the information society where jobs are no longer long-term, but depend on tasks to be fulfilled, and the approach to competence needs to be adjusted, based on automated application processes, used in production, to enhance the adaptability of personalities.

Qualification is officially recognised competence, i.e. there has been assessment and it is evidenced by a certificate and a register. Qualification, required at work-place, may be lower than the real competence of the person concerned.

Based on information era requirements, the definitions of competence, competency and qualification are summed up in the best possible way by the term occupation.

3.2 Learners’ Self-Regulation Theory

Self-regulation is one of the central issues of engineer studies. Self-regulation implicates ideas, feelings and actions that are planned and linked, cyclically, to the achievement of personal goals [88]. Meta-cognition plays an important role in learning. In addition, the way we assess ourselves and affective reactions also have some influence on self-regulation, for example, doubts (lack of faith) and fears that are linked to performance situation. The ay we assess ourselves also covers self-efficacy – a learner has his/her own vision of his/her organisational abilities and performance of actions that are needed to cope with a specific duty – explaining the individual’s motivation to adjust his or her performance [89].

Students, working with self-regulation, are therefore actively participating in learning process: they adapt their ideas, feelings and activities to meet the objectives, established for learning. S/he plans activities and obtains feedback during learning process, observing the efficiency of learning methods and responding to feedback gained. Zimmermann [90] states that “learning is not something that happens to a learner, instead, this is something that a learner makes to happen”. Therefore, learning outcomes are also expressed outside the learner him/herself.

According to socio-cognitive theory, self-regulation is linked to situations. The skill of self-regulation is therefore not a general characteristic/alacrity or development level achieved. Also, not all learners do regulate, studying all subjects or different fields, their activities in the same way [91]. Whereas certain self-regulation processes (for example, establishment of an objective) can be applied in numerous different situations, a learner must understand how these processes can be efficiently managed for learning different subjects and themes.

Self-regulation rely on the assumption that learners are aware of the influence of self-regulation processes on learning outcomes. Different theoretical trends are, however, characterised by different details. Zimmermann [92] compares different theoretical approaches to self-regulation, applied during learning, and characterises each theory according to the solution that it offers to the following questions:

- What motivates learners for self-regulation?

- Which processes help to develop learners’ perception of themselves?

- Which key processes do learners use to achieve their learning outcomes?

- How is learner’s self-regulation influenced by social and physical environment?

- How can a learner develop his/her self-regulation?

Shortened version of answers, given to these questions, is assembled into table (Tabel 3.1). Only some of the approaches, describing self-regulation, are discussed below.

- Learning is a cyclical process, involving learners observing the efficiency of learning strategies and responding, using self-control, to the feedback that they’re given. The feedback may include invisible change in interpretations concerning “me” or some visible changes in one’s actions, for example, replacing one learning strategy for another. Phenomenological aspect emphasises changing interpretation levels in ‘me’-evaluation, interpretation of oneself and self-actualisation. The aspect of operant conditioning pays attention to specific details, for example, the use of memory techniques, controlling one’s activities and self-awarding or strengthening.

- Self-regulation theories open aspects and explain the reasons, how and why learners adopt certain self-regulation process, strategy or reaction. According to operant conditioning theory, in the case of self-regulation we’re dealing, in conclusion, with controlling external award or punishment contingencies. According to the phenomenological approach, learner is motivated by self-evaluation or self-interpretation. Between these two extremes we can fit a number of theories that emphasise the success experiences, reaching objectives, self-efficacy and assimilation of definitions.

Table 3.1 Self-regulation processes in different theories (Nissilä, S-P [93] referring to Zimmermann 1998; 2000;2001)

| Theoretical aspect | Motivation | Self-understanding | Key process | Social and physical environment | Self-regulation ability and development of skills |

| Operant conditioning | Reinforcing irritation | Won’t pay attention, except self-reactions | Self monitoring, control and evaluation | Model learning and reinforcement | Shaping behaviour and elimination of unimportant irritants |

| Phenomenological theory | Self-actualisation | Role of me-image | Self-respect and me-identity | Subjective observations within environment | Development of me-constructions |

| Informational processing | Information with emotional colour | Cognitive self-monitoring | Information processing and storage | Influences on information processing | Developing the alacrity, needed to process information |

| Socio-cognitive theory | Efficiency appraisal, expectations regarding outcomes and objectives | Making observations about oneself and monitoring | Making observations about oneself and reactions | Model learning and learning based on incidental experiences | Development as an outcome of social learning |

| Deliberation, intent | Expectations/values (pre-requisites for deliberate action) | Control of action (not as much control of psychological condition) | Cognition, motivation and emotion control strategy | Controlling disturbing factors in learning environment | Developing the pre-requisites for the implementation of deliberate strategies |

| Constructivist theory | Solving cognitive conflicts and curiosity | Meta-cognitive observation | Construction of schemes, strategies and individual theories | Solving social conflicts and creative learning | Restrictions to the implementation of self-regulation processes by development stage |

- Different self-regulation theories give different answers to the question, why learners succeed or fail with their self-regulation. For example, constructivist approach emphasises the development levels of meta-cognitive alacrities, while cognitive theories emphasise learner’s different interpretation of usefulness of strategies and the wish to apply certain strategies, identified with this interpretation. Socio-cognitive theory pays special attention to self-efficacy, expectations to outcomes and the role of objectives in learning [61].

- Development of self-regulation skills requires practice. When learners don’t consider the acquisition of such skills as important, they have also no motivation for self-regulation. Different theories differ by outcomes they emphasise. For operant conditioning, the focus is on external outcomes while other theories focus in internal outcomes, for example, achievement of success or management experiences. Phenomenological theories, however, like constructivist theory, consider the development of learner’s identity to be important and also its role in improving learning motivation [61].

Self-regulation is highly important for learner’s activities, it is needed to survive and to achieve one’s objectives and realise dreams with quality, in other words, to lead a better and higher quality life.

Basic knowledge and skills, needed for self-regulation, form a certain model or platform (page 83), which the parties, involved in learning process, can jointly use for mutual communication and information and data exchange involved. One singularity must be considered when comparing students of technical specialties to other students – they need a language more schematic, drawings, diagrams and models, as this method of comprehension is more natural for them.

3.2.1 Self-regulation Model

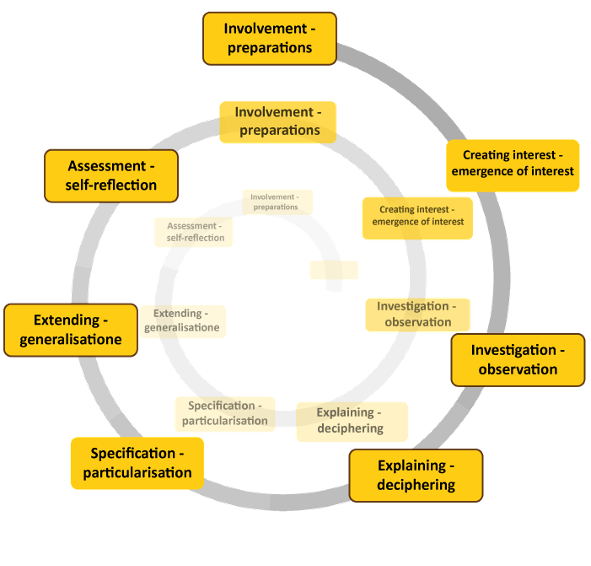

Learning, based on self-regulation platform, is often observed as a cyclical process. This is a contemporary method; seven time-related stages can be observed in the cycle, similarly to the 7E learning process model:

- Involvement – preparations, acknowledgement of the question raised

- Creating interest – emergence of interest and attention

- Investigation – observation, getting the wow-experience

- Explaining – deciphering

- Specification – particularisation

- Extending – generalisation and using the learnt information beyond the current limits

- Assessment – self-reflection

Pintrich (2000) classifies the spheres of self-regulation, additionally, depending on whether we’re dealing with regulation covered cognition, motivation/affect, behaviour or context [86]; [94]. Diversity of self-regulation is illustrated by Table 3.2.

The periods of preparation and creation of interest also include the period of planning and activisation and here we can distinguish analysis of learning task and assessment linked to self-regulation. Good self-regulators study the material to be learnt, establish themselves personal objectives and consider the strategies that would be most useful for learning. Motivational assessments also include self-efficacy and expectations with respect to outcomes.

Table 3.2 Links between self-controlled learning stages and spheres of self-regulation, goal-orientation and internal interest [86]; [95].

| Stage | Cognition | Motivation/affect | Behaviour | Context |

| Involvement – preparations | Establishment of an objective acknowledgement of ‘why’ question (acknowledgement of the problem) | Goal orientation Effectiveness assessmentImage of simplicity and complicacy of the learning material | Planning efforts and time-managementPlanning self-control activities | Definition of a taskDefinition of context |

| Creating interest – emergence of interest | Activisation of meta-cognitive knowledgeActivisation of earlier learning experiences | Importance and meaning of learnt materialEnhancing interest | Launching efforts and time managementLaunching self-control activities | Looking for links between tasks and real world |

| Investigation – observation | Observation of meta-cognitive knowledge | Observation of motivation and emotional status | Making efforts and experimenting with time management and monitoring need for assistance | Observing the contents of a task |

| Explaining – elucidation | Choice of a cognitive strategy needed to regulate thinking and learning | Choice of strategy needed for motivation and management of emotional condition | Elucidation of learning processUse of well-known terms, definitions and theories | Elucidation of a task |

| Specification – particularisation | Implementation of a cognitive strategy, needed to regulate learning and thinking | Implementation of a strategy needed for motivation and management of emotional condition | Increasing/decreasing effortsParticularisation of theoryPersistence, giving up | Changing or explaining the task |

| Extending – generalisation | Attributive assessments | Affective responses | Looking for assistancePresentation and use of the results achieved | Changing the context and withdrawal from the situation |

| Assessment – self-reflection | Cognitive assessments | Affective responses | Considering alternative activities | Assessing the taskAssessing the context |

Learner’s self-efficacies facilitate his/her motivation to remain committed to self-regulation and carry out self-control, self-assessment and identification of goals. Expectations with respect to outcomes (faith regarding the outcomes to be achieved) will give motivation for self-regulation if positive while negative or insecure expectations with respect to outcomes will inhibit self-regulation. Learners oriented on goals, emphasising the development of competence (learning objectives), are more successful than those competing for achievement or grades (performance objectives). Internal interest will help to continue efforts needed for learning even if there is not external support and encouragement available.

Action control or management strategies will help learners to focus on task at hand and optimise their performance. By directing one’s attention and focusing, learners defend their will to learn, defend themselves against different disturbing factors and competing wishes. Focusing on what’s important will also offer protection from disturbing factors in the environment [97]. Learners will make their decisions regarding the learning method and strategy. S/he may test his/her skills, by asking oneself questions or using mental images. Proficient learners can exercise self-management, mental images, time management, organisation of learning environment and employ the assistance of others in learning process. The efficiency of strategic processes will depend on self-observation: learners must observe not only their own activities but also the surrounding conditions and their possible influence. In relations with he surrounding, it’s important for students to create visual images of their mental images or use the visualisation tool.

Self-observation and also keeping an eye on the context will help individuals to obtain information about their development. Of course, observing one’s activities can also distract and the learning process may therefore suffer. Form the other hand, skills that have become proficiency will require less and less deliberate monitoring and the implementation of a skill will become a routine or automatic. As a consequence, self-observation will be transferred to a more general vision (or level or goal) and also to sub-conscious level, relating oneself (like an onlooker) to learning environment (external context) and outcomes of one’s activities. Development of permanent habits will allow to direct activities that were originally conscious, to sub-conscious level.

Students with poor learning skills; those unable to visualise strongly enough, having a weak discipline where it comes to the implementation of mental goals (limited internal peace) or unable to match their objectives (for example, processes, tasks and works with more specific applications), may become overloaded with detailed information. Their internal feedback may be overloaded. Central self-control form includes taking notes and writing down problems.

Figure 3.3 Learning, based on self-regulation, using 7E model

The self-reflection stage is divided into self-assessment and reflective reactions. In the case of self-assessment, an individual will compare information, obtained by self-observations, to external standards or objectives. S/he wants to obtain quick feedback on how s/he has done with achieving objectives, established for others or him/herself, compared to other learners. Attributive interpretations are linked to self-assessment: learners will try to interpret the reasons for their successes or failures. For example, they may blame their failure on their lack of talent or too little effort or losing the focus.

Attributive interpretations may also take to positive reflective responses (self-reactions). Learners may interpret too little effort as the reason of their failure and therefore, make even more effort. However, if they blame their own limited abilities for their failure, responses will be negative. Attributive interpretations also show what could be the possible reasons of mistakes, made in the learning process [98]; [87]. Positive reactions will strengthen positive interpretation of oneself as a learner, for example, faith in one’s abilities and opportunities, learning orientation and internal interest in the task at hand. Commitment to a task will be also improved.

Experiencing peace or success is an important process, related to self-reactions, as people are willing to commit to a learning that will result in positive feelings and experiences. From the other hand, they attempt to avoid negative emotions and feelings, for example, fear of failure [89]. Another form of self-reaction may be adaptive or defensive model of action. Good self-regulators can adapt the model to the situation and circumstances [99]. Poor self-regulators attempt to hide from disappointment and protect themselves. Defensive responses are, for example, helplessness, delaying, avoiding the task, cognitive non-commitment and apathy [100].

3.2.2 Summary

Self-reflection stage of the learning process may result in updating the applied modus operandi, questioning the former routines and getting them replaced for new routines that match the circumstances better. Efficient methods are visually structured and diversified, allowing for diversified observation.

For example, students may visualise their self-regulation models. Visual model allows to analyse and identify mistakes in the self-regulation algorithm. For example, everybody wants to achieve success, but may will avoid failure at the same time and are therefore afraid to take any action (to make the first step).

It’s obvious that once new knowledge is obtained, the scope of practical experiences is still limited. Those striving for quick success must first overcome failure and only then, success can be achieved.

Investigation and Analysis of Competence-based Education of Students of Technical Specialties

Development of self-regulation skills

When observing the development of self-regulation, we encounter many disturbing factors that have been discussed in different studies, in universities. Unfortunately, this topic has not been studied much. Several barriers, known as the “barriers to learning”, are encountered in the learning process. For learning as a process to continue, it’s important to overcome the barriers to learning. In Estonian language, “barrier” means an obstacle, an obstruction [5], and therefore, obstructions to learning are defined as barrier to learning.

In universities, learning takes place, on long-term bases, within a formal learning environment, involving formal rules and restrictions, and students must cope with changes in academic behaviour, which also involves overcoming certain barriers. Context of a university requires, compared to earlier studies, more responsibilities and taking personal control of learning and students have no complete overview of the situations that really take place in the university [101].

In university, barriers to learning incur frequently, due to long study period, formal environment and academic behaviour. Therefore it’s important for the students to understand the nature of barriers to learning and factors that may cause them, and the lecturers being able to support students in overcoming the barriers to learning. Student and lecturer should co-operate for the purposes of learning process [102]. The best possible way for lecturers to support students is to teach them self-regulation skills, like self-management [101]. To develop self-regulation in students, lecturers should develop more efficient learning strategies, like planning, control and guiding learners to analyse their work [103]. This means that students must understand – responsibility in coping with barriers to learning lies with him/her and lecturer can only support the processes for overcoming the barriers.

Barriers to learning are studied within three different dimensions, as follows [104]:

- emotional (characterised by resistance to learning);

- cognitive (wrong learning can incur);

- social (there are limitations to oneself, mental defence against learning).

Regardless of the fact that the barriers to learning may incur in various dimension of learning or at the same time in all three, table 3.3 has been prepared, providing an overview of the types of barriers to learning to be distinguished, their nature, reasons, possible forms of expression and the ways for supporting students [105].

Table 3.3 Overview of types of barriers to learning, their reasons, forms of expressions and alternatives for supporting coping [105].

| Type of barrier to learning; identifying dimension | Nature of barrier to learning | Reasons causing barriers to learning | Expression of barrier to learning | Possible available to lecturers for supporting overcoming the barriers to learning |

| EMOTIONALDefence against learning (defence of regular consciousness, defence of identity, defence against the feeling of fatigue | Defence mechanisms for maintaining mental balance | – Factors that threaten, limit, violate the maintenance of mental balance- Changing identity- Learning impulses that we encounter on daily bases- Authorities indulging inappropriate behaviour with no reason (dictatorship), lack of democracy (unpleasantness)- Helpless in a given situation | – Underestimation- Harmonisation- Rejection- Scapegoat mechanism (projecting)- Anger- Sadness- Despair- Low self-esteem- Opposing behaviour towards authorities | – Motivation- Development of will- Offering positive emotions- Accommodation and understanding- Fair treatment- Step-by-step changes- Giving freedom of choice- Involvement in decision-making process- Linking tasks to practice- Making compliments- Avoiding accusations- Giving an opportunity to express things we’re proud of- Supporting in overcoming fears- Communication both in school and outside curricula |

| COGNITIVEWrong learning | Students don’t understand what knowledge the lecturer is attempting to convey or students interpreting information in a way different than conveyed by the lecturer | – Gaps in earlier knowledge- Excessive involvement/time problems- Fear of knowledge outcomes- Excessive interpretations in text- Misunderstandings- Leaving learner “alone” in the learning process- Unawareness of what is right and what is wrong | – Misunderstanding- Failed focusing- Non-understanding- Inability to grasp the information- Cocky attitude – students assuming that they know enough about the material | – Expressing support and understanding- Attaching meaning and importance to the materials for the student- Clear and unambiguous expression of oneself- Avoiding giving too much information too quickly- Using techniques that facilitate focusing- Encouraging to ask questions- Explaining the benefits, provided by learning process- Pointing attention to development issues of students- Involvement of students- Acknowledgment of students’ expectations |

| SOCIALResistance to learning (active resistance, passive resistance) | Fear of changes that result from learning and are considered unacceptable by the student | – Modesty and restrain in self-improvement process- Conflict situations- Applying pressure- Unpleasant subject/teacher/mentor- Acquisition of new ideas/skills/ understandings- Attempt to restore inner balance- Reality does not coincide with earlier experiences | – Resistance to co-operation with mentor/instructor- Disturbed orientation within the learning environment and stability- Confusion- Frustration- Cognitive and emotional problems- Anger/rage- Aggression- Wanting something else | – Facilitation of communication and co-operation- Respecting the experiences, coming with changes- Supporting changed understanding- Maintaining hope and motivation- Supporting overcoming the earlier negative experiences- Teaching self-regulation skills- Avoiding pressure- Asking students for feedback- Giving freedom- Visual description of action plan |

Supporting overcoming emotional barriers to learning mostly involves overcoming the defences. According to Illeris [106], the alternatives for overcoming emotional barriers to learning are related to motivation, developing will and offering positive emotions.

Supporting overcoming cognitive barriers to learning mostly involves overcoming the problems of wrong learning. As wrong learning is deeply internal process of a student, it’s very difficult for lecturers to recognise the issue and then support the student in overcoming the barrier [107]. The alternatives for supporting wrong learning mostly involve avoidance of gaps (in knowledge) and supporting understanding, focusing and positive aspects [105]. Getting practical experiences is also of big help.

Supporting overcoming social barriers to learning mostly involves overcoming resistance. The lecturers can help in overcoming resistance in students by supporting communication, avoiding limited objectives (have the courage to dream!) and overcoming earlier negative experiences by using visual examples.

3.3.1 Summary

Coping with barriers to learning is mostly related to the abilities of lecturers to develop self-regulation skills in students and their own empathy. Lecturers can’t support students with overcoming barriers to learning, if the students don’t understand the importance of self-regulation and the principles for its implementation. Therefore, it would be necessary for a lecturer to pay attention to self-regulation skills, seeing that a student is acknowledging and controlling his/her behaviour, feelings and thoughts, to achieve the required academic goals [108]. The chapter can be summarised as follows, based on the conducted analysis and studies [105]:

- Self-regulation skills of students need to be developed for the students to be able to take control of their learning and establishment of objectives, thus making it easier for them to overcome the possible barriers to learning. By doing this, the barriers to learning will be overcome by the student and lecturers will only support students in the process for overcoming the barriers to learning.

- For that purpose it is necessary to give the students and lecturers general yet visual picture of the learning process, learning and teaching. Studies have shown that lecturers and students are unaware of real self-regulation processes in education, learning, reasons for the barriers to learning and the ways for coping with the barriers.

- For improving the efficiency of learning, a student must be capable of better structuring and visualisation of mental images. It is also useful to visualise real activities and functions, not just geometric objects. Weak links of spatial performance (activities) of framework structure of geometrisation processes to the framework of describing geometric objects (x,y,z-axes) can become a problem here.

- Visual teaching materials can be used efficiently to search for problems to emotional, cognitive and social problems.